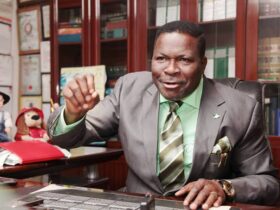

By PROF. MIKE OZEKHOME, SAN, CON, OFR, FCIArb, LL.M, Ph.D, LL.D, D.Litt

INTRODUCTION

Having discussed the many reasons why Nigeria must tarry about leading any war against Niger in part 3 of this treatise, we shall now discuss the critical issues regarding sovereignty in International Law, the UN and Regional Agencies, Nigerien Sovereignty and the International Laws and Instruments that govern wrongful Intervention.

SOVEREIGNTY UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE THREAT OF WAR

Sovereignty is the absolute power of a state to control and manage the affairs within its territory without any form of external control. Implicit in this definition are the concepts of equality of States and the territorial integrity of all States. These concepts are contained in the Charter of the United Nations, 1945.

The preamble to the Charter of the United Nations, 1945, clearly highlights the objectives of the Charter. The first paragraph in the preamble to the Charter started with a reminder of the scourge of war that had twice brought untold hardships to mankind. This was why parties to the Charter agreed to:

practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours;

unite their strength to maintain international peace and security, and to ensure, by the acceptance of principles and the institution of methods, that armed force shall not be used, save in the common interest; and

to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples.

Article 1 of the UN Charter reaffirms the purpose of the United Nations, which is to maintain international peace. Article 1(4) thereof states clearly that:

“All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”

Paragraph 7 states that:

“Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorise the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state or shall require the Members to submit such matters to settlement under the present Charter, but this principle shall not prejudice the application of enforcement measures under Chapter VII”

Chapter VII of the UN Charter provides instances where the UN might intervene in matters which are within the territorial integrity of a State. Such instances which are entrusted to the UN Security Council are with respect to threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression; all of which are considered as threats to international peace and security. However, under Article 39, it is the UN Security Council (UNSC) that has the sole power to (1) determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression; and (2) make recommendations; or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance with Articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such measures include complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations. Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations. Going by the provisions of Chapter VII, the use of force is the last option/measure to be taken or implemented.

Article 51 provides:

“Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security”.

In the First Hague Convention of 1899, the signatory states agreed that at least one other Nation be used to mediate disputes between states before engaging in hostilities.

Title II, Article 2

In case of serious disagreement or conflict, before an appeal to arms, the signatory Powers agreed to have recourse, as far as circumstances allow, to the good office or mediation of one more friendly POWERS

THE 1907 HAGUE CONVENTION

The Hague Convention (III) of 1907 called “Convention Relative to the Opening of Hostilities” gives the international actions countries should perform before hostilities. The first two Articles say:

Article 1 thereof provides that

“the Contracting Powers recognize that hostilities between themselves must not commence without previous and explicit warning, in the form either of a reasoned declaration of war or of an ultimatum with conditional declaration of war”.

THE UN AND REGIONAL AGENCIES

Members of the United Nations are independent States. Their right to join or establish regional agencies for dealing with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace is guaranteed under Chapter VIII of the United Nations Charter. This is where ECOWAS comes in. However, under Article 52 (1), such arrangements or agencies and their activities must be consistent with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations.

Further, Article 52 encourages the UN Members entering into such arrangements or constituting such agencies to make every effort to achieve pacific settlement of local disputes through such regional arrangements or by such regional agencies before referring them to the Security Council. Nothing in the Charter gives them any express or implied authority to use force or invade any country under any guise. This power resides only with the UN Security Council. As a matter of fact, Article 53 thereof provides expressly that:

“The Security Council shall, where appropriate, utilize such regional arrangements or for enforcement action under its authority. But no enforcement action shall be taken under regional arrangements or by regional agencies without the authorization of the Security Council* with the exception of measures against any enemy state, as defined in paragraph 2 of this Article, provided for pursuant to Article 107 or in regional arrangements directed against the renewal of aggressive policy on the part of any such state, until such time as the Organization may, on request of the Governments concerned, be charged with the responsibility for preventing further aggression by such a state. 2. The term enemy state as used in paragraph 1 of this Article applies to any state that during the Second World War has been an enemy of any signatory of the present Charter.

Further, Article 54 provides that:

“The Security Council shall at all times be kept fully informed of activities undertaken or in contemplation under regional arrangements or by regional agencies for the maintenance of international peace and security”.

It is therefore clear that neither the AU nor the ECOWAS as Regional Agencies can take unilateral military action against the Niger without the UN Security Council.

SOVEREIGNTY OF NIGER REPUBLIC

The sovereignty of a Country is the most essential attribute of that Country in the form of its complete self-sufficiency in the frames of a certain territory. It is its supremacy in the domestic policy and independence in the foreign one. It is the authority of that Country in her decision-making process and in the maintenance of order, outside the intervention of international powers. Niger Republic is a Sovereign State and regional powers such as the AU and ECOWAS are limited in their intervention in the internal matters of a sovereign State like Niger Republic. It must be emphasized that political independence and territorial integrity remain major planks of International Law, International Relations and Diplomacy.

In the case of MARWA & ORS V. NYAKO & ORS (2012) LPELR-7837(SC) (PP. 147-148 PARAS. E), the Supreme Court held on sovereignty thus:

“I would start by saying that there are two forms of government; de facto and de jure. De jure is a government in law; and de facto is a government in fact. A government recognised as de jure government is the one which ought to possess power of sovereignty although at that time it may be deprived of them, whereas a government recognised as government de facto, but recognised dejure is one which is really in possession of powers of sovereignty although the possession may be wrongful. A de facto government is supreme in all internal matters and its internal acts are internationally valid, it can sue and be sued in courts of recognising states, it is entitled to immunity from judicial process, but in external matters the de jure government is supreme. See the U. S. Supreme Court decisions in Texas v. White 1. 19 law Ed. U. S. 74 – 77 at 2410; Luther v. Sagor (1921) 1 K. B. 456; The Atanizanza Mendi (1939) A. C 236; Banko De Bilbawo v. Sancha (1938) 2 K. B. 176.” Per MUNTAKA-COOMASSIE, J.S.C.

ECOWAS might argue that it is coming under the standby Force which is an operational multipurpose structure provided for under the Protocol on Mutual Assistance in Defence signed in Freetown on May 29, 1981, (now known as Protocol Relating to the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peace-Keeping and Security, promulgated in 1999). However, we must state categorically that military intervention by ECOWAS does not fall under this purview. The said regional Standby Force’s functions are limited to observation and monitoring; peacekeeping and restoration of peace; humanitarian interventions; enforcement of sanctions-including embargo; preventive deployment; peace building; disarmament and demobilisation; and policing activities- including the control of fraud and organised crime. These do not include intervening in the political and domestic structure or affairs of a member state.

INTERNATIONAL LAWS AND INSTRUMENTS GOVERNING WRONGFUL INTERVENTION

One might wonder where the ECOWAS derives the legitimate authority to breach the territorial integrity of the Nigerien borders, in spite of that of the doctrine of sovereignty which posits that no nation or international organization shall interfere in the domestic affairs of another. In the light of this, Article 2 (4) of the United Nations governing Constitution provides thus:

“The Organization and its Members, in pursuit of the purposes stated in Article 1, shall act in accordance with the following principles. … 4. All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations”.

The action of ECOWAS’ proposed Military intervention in Niger Republic is therefore expressly by the above provisions of the UN’s Constitution.

The current global security order was fashioned out after the gruesome and horrific experience of World War II, when the twin Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed by the first atomic bomb; and when human misery escalated due to the atrocities visited on mankind by the war. The UN Charter thus vests the UN Security Council (UNSC) with the primary mandate to maintain international peace and security. The Charter prohibits the use of force, or threat of force against the sovereignty and territorial integrity of any state. Under Article 53 (1) of the UN Charter, only the UNSC can authorize the use of force for collective security where it has been determined that there is a threat, or breach of peace, or an act of aggression anywhere in the world, including amongst regional bodies and agencies. This is not the case here. (To be continued).

Leave a Reply